The VT Agency of Natural Resources was asked to prepare a report on the Maple Sugar Industry by the House Committee on Natural Resources, Fish and Wildlife. A link to the report may be found here.

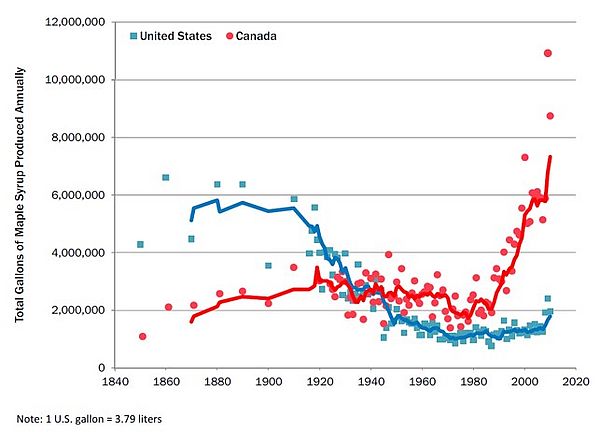

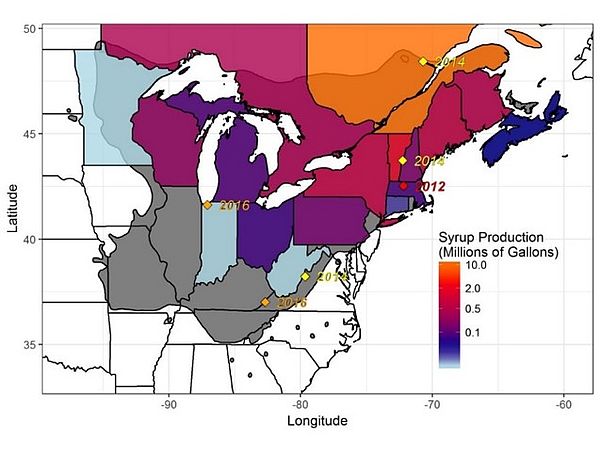

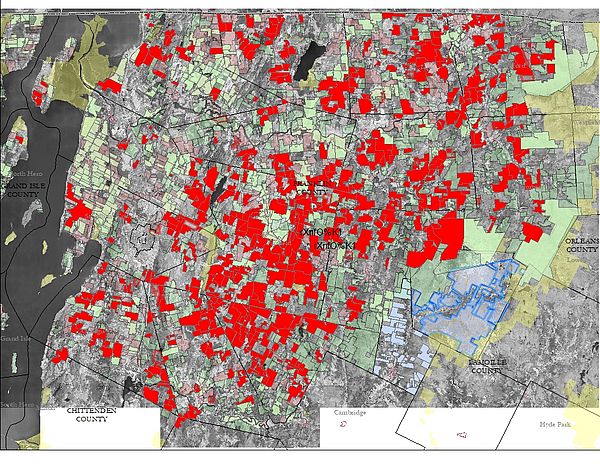

Vermont is the largest producer of maple syrup in the United States. Note: Canada can claim 90% of the world market. Closer to home, the maple industry has been disproportionally located in Franklin County. This is due to several factors both ecologically and culturally. Throughout the colonial period of Vermont's settlement most all farms had a subsistence sugarbush, which had a factor in the proliferation of maple as the forest re-established on previously cleared land. Franklin County is arguably the most agricultural county in Vermont. The presence of a large farming community that persisted long past other counties allowed the workforce and family tradition of sugaring to become a natural phenomenon for farm families in Franklin County. Ecologically, the soils here are enriched with Calcium and Magnesium, important for optimum maple growth. Up to this point Franklin county has annually produced twice as much syrup as the rest of the state combined. Sugaring operations from 200 taps to 200,000 taps can be found in this part of the state Approximately 30% of the Use Value Appraisal (UVA) enrolled forested landscape in Franklin County is tapped. If the forested wetlands and conifer cover is deducted, the area is closer to 50% of the Hardwood enrolled in UVA.

Because of the large presence of the maple industry on our shared landscape, CHC has decided to respond to the agency report in this newsletter. Maple sugaring has changed dramatically in the last 20-30 years with changes to the economy, demand, and technology of collecting and processing sap. In addition, increasingly larger operations expand here and across the state. Producers now include both the family owned operations that we are familiar with in Franklin County as well as investor owned operations. Some of these investor owned operations are controlled by interests outside our communities, including across the border in Canada.

CHC supports the maple syrup industry. This industry has created new revenue streams for landowners, helping our forests remain economically viable (keeping forests as forests). It has provided a multitude of employment opportunities for our friends and neighbors. And it has helped connect people near and far to our corner of the Northern Forest. We also feel it is important to address some big questions on how the industry is changing, and what that means for our woodlands. We feel that asking the hard questions will result in better policy resulting in healthier, more productive woodlands

Questions to Raise:

1. What does the state consider large scale or industrial scale sugaring?

This is a complicated question. Does this follow by number of taps or by the management practices implemented? In Franklin County large scale is often owned by families with 3 or more generations involved. This is the result of long term tradition becoming a way of life and an economic livelihood. On the other hand there are large operations whose ownership is not local, or do not have a working landscape tradition. As Canada implements a quota system on production, are Canadian companies buying land in VT to avoid the quota?

2. What effect does large scale sugaring have on the ecosystem and Ecosytem services?

This question is also difficult to answer. The Use Value Appraisal program and Vermont Organic Farmers Association have a set of standards that must be followed that address some issues of diversity of species and structure and work to mitigate and allow our forests to adapt to climate change. The Bird Friendly maple program with Audubon VT also addresses some ecological criteria. There is, however, another segment of the maple industry that is not required to follow these standards. With the rapid expansion, treating the forest for sugaring has taken on a new look. Many producers who plan to convert a forest to a sugaring operation may harvest the stand heavily at first, with plans to not harvest again for some time. The result could be sedge, fern, or early successional species, essentially setting the forest back a few generations. Some sites are chosen to tap that are not very suited to maple: Hydric soils, nutrient poor soils, Hemlock or spruce dominated forests. Once tubing is up, harvesting becomes harder to implement and some producers prefer not to cut trees at all. On sites with poor nutrient capacity this may result in a beech understory. Finding a way to meet the requirement of UVA, while maintaining both ecological integrity and maple production can be tricky for some owners.

3. How does sugaring affect the timber economy?

Sugarbush management in UVA requires landowners to use the accepted silvicultural guides that are based on natural stand dynamics with a timber management goal. This is to ensure that all options remain open for management of this forest over the long term. Silvicultural treatments address the site and growing conditions of each forest stand and harvesting is required in a managed forest to meet the goals of a landowner. Thinking about regeneration is critical in maintaining a healthy forest. A sugarbush is intensively managed and cannot be treated like a wilderness area. Our maple is one of the most valuable species for furniture and flooring in the world. Tapping maple degrades the quality of the trees for lumber. Most importantly, the extensive and high tech tubing can prevent or delay harvesting due to difficulty of machine access. An issue that comes up frequently is how we assess the quality of the trees in the forest. Following sound management practices harvesting should maintain or increase the amount of high quality trees. Doing otherwise is considered high-grading which degrades the long term condition of the forest. Acceptable growing stock has been traditionally determined by the timber value. This has been linked in management recommendations to the scientific study of natural stand dynamics. In a natural system over time trees grow mostly straight and tall with defective and diseased trees declining first. Allowing a poor formed or multiple stemmed tree to be considered acceptable would harm the long term health of the forest, and limit the options for future owners of the land.

4. What does organic sugaring look like in VT?

People are always asking why maple syrup is not automatically organic. It is because it is a wild crop, and so needs to be managed within the context of the broader ecosystem. The sugarhouse also needs rules on cleaning materials, pest control and defoamers. Vermont Organic Farmer's Association and the Department of Forest. Parks and Recreation teamed up to make our standards compatible. The criteria includes developing and maintaining species diversity, and diversity of structure; managing for all age classes; using appropriate tapping methods; and considering the site. There are however other organic certifiers that are located outside the state of VT with very little forest management criteria. It is important as the industry grows (both on the individual operation scale, and the Vermont scale) the certification of organic is not diluted under certifiers that do not connect the ecosystem health with the product.

5. How does sugaring impact public recreation?

The modern day tubing installations are now the norm in the industry. The efficiency of this system is critical to the ability of the expansion we have seen. Only the very smallest hobby owners use buckets. While buckets came down annually, tubing stays up permanently. For tourists coming to the state, the amount of tubing in the forest does not correspond to their romantic notion of what sugaring is, and it may also detract from seeing the forest as a natural environment to enjoy for its beauty and ecological benefits. The timber industry has faced similar issue in the past but harvesting occurs intermittently, not annually, and usually only the intensive harvesting is noticed by visitors. The tubing system also limits movement by hikers, skiers, and mountain bikers. Careful planning and layout of trails to allow for access will be critical on the landscape where we wish to maintain mixed use areas, and support the growing outdoor recreation economy. Recreation is also a growing industry fueling economic growth in our communities.

6. How does sugaring affect wildlife habitat movement?

There is really no research on this issue, but moving through a tubing system would be impossible for large mammals (just ask any sugarmaker who has had a moose in their sugarbush). White tailed deer have to go under and over the lines, expending more energy. The deer may learn to avoid these areas putting additional pressure elsewhere or suffer nutritional decline. More needs to be studied to understand the impact of tubing on wildlife habitat.

7. How does maple sugaring impact Water Quality?

Again, more research is necessary about extraction of sap at higher rates using vacuum systems. Is there a decrease in the water availability? The other question is how the water that is removed through the reverse osmosis system gets reintroduced back into the environment. When water was removed only through boiling the sap all the water returned to the system as vapor into the atmosphere. With reverse osmosis the water is in liquid form and removed as a point source. This water is warmer than the environment and is distilled. A large flow of warmer distilled water may impact stream biotic health depending on how it is released. A large flow may also impact water quality if it causes the movement of sediments into streams. Roads and trails in a sugarbush are used annually in a time of year that can cause concern. Neither agriculture AAPs nor Forest Management AMP's currently address sugaring roads.

8. What does large scale expansion mean for infrastructure?

Similar to the use of forests roads and trails, the increase of large scale operations means an increase in truck traffic over our local roads to haul sap in a season where roads are most sensitive to damage. While most of our town roads remain posted through early March and April, sap is treated as an agricultural product and is exempt from the prohibition on heavy weight travel. This causes concern for emergency vehicle access and the cost of road repair paid through local taxes. In contrast to milk trucks, which are generally found in the valley, sap trucks are often in the higher elevations on lower grade roads. It needs to be determined what the environmental impacts are of degraded road conditions caused by sap hauling, and whose responsibility it is for cost of maintenance.

In summary, the expansion of sugaring in our region holds great promise, but it also raises great questions that we, as stewards of our forests and members of communities, will need to address. If we wait to ask the questions, we may miss important issues and the ability to prevent potential problems.